Loading

Sources of Truth in Religion

The term 'religion' finds its roots in 'religate,' meaning to bind together, depicting it as a framework explaining the connection between humanity and divinity. This connection relies on the existence of a soul, the essential, immaterial part that endures beyond the body's death. Without a transcendent foundation, religion loses its deeper meaning, reduced to one of many considerations in earthly life. The idea of a greater order, beyond human comprehension, parallels how science envisions a pre-universe existence without space, time, or matter. Religion, then, is seen not as a destination but a pathway to a greater truth, bridging the gap between humans and the transcendent. Arguments against religion often challenge its fundamental premise, positing a purely materialistic explanation for existence. While some critique religion based on its followers' actions, the essence of the truth it seeks to convey remains distinct from its flawed human representations.

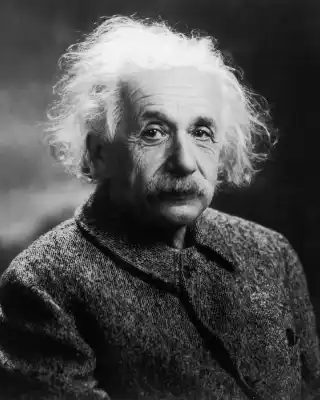

Albert Einstein's writings reveal a nuanced perspective on religion, distinguishing between various stages of religious thinking. For Einstein, religion goes beyond an acknowledgement of human limitations; it is a devotion to something greater than the self. He views great moral teachers as artistic geniuses in the art of living, suggesting that religiosity is not just a stated belief but an inseparable part of how one perceives and lives life. Religion, according to Einstein, is meant to be lived and demonstrated rather than merely professed as an idea.

Racism, at its core, is a psychological disease rooted in the human tendency to magnify minor differences and externalise inner conflict. While race has no basis in biology or genetics, it persists as a social construct, fueled by humanity’s compulsion to categorise and affirm superiority. Drawing on Freud’s concept of the 'narcissism of minor differences' and the biblical story of Cain and Abel, the article explores how jealousy, insecurity, and self-hatred manifest as prejudice and violence. Like a poisonous weed in the garden of humanity, racism spreads and chokes unity, but it can be addressed through empathy, understanding, and persistent effort to nurture a world defined by our shared humanity.

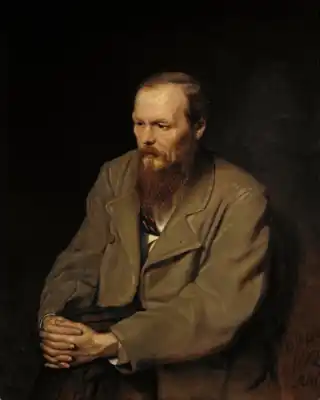

Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s exploration of morality in 'Crime and Punishment' delves into the tension between self-interest, reason, and true moral conviction. Through the character of Rodion Raskolnikov, who rationalises the murder of a moneylender as a means to benefit society, Dostoyevsky exposes the fragility of moral justifications rooted in convenience rather than steadfast principles. Raskolnikov’s inability to adhere to his proclaimed utilitarian reasoning, especially when faced with unforeseen challenges, highlights how self-interest can obscure moral clarity. The contrasts with religious narratives, where figures like Job and Jesus embody unwavering moral integrity despite adversity, suggesting that true morality transcends personal gain and may require a foundation in faith or transcendent values.